Posted on 18th August 2015

Lessons Learnt from a Participatory Design Workshop

On 28th of July 2015, the Leeds Beckett Autism&Uni team held the first in a series of participatory design workshops with young autistic adults. We tested prototype content, formats and different media for an interactive toolkit.

This toolkit will be one of the main outputs of the Autism&Uni project, helping young people on the autism spectrum navigate their way into higher education.

We recommended that participants bring a parent or friend if that made them feel more comfortable, but made it clear that we wanted to hear the young autistic people’s views and not others speaking for them, and this worked well.

We created a full workshop briefing document in advance of the day, with lots of pictures (of Marc and Penny, the buildings and rooms we were using and photo directions to the meeting point) and structured text information. This is where it helps to have an autistic researcher working on the project – Penny put in the information she would need and want!

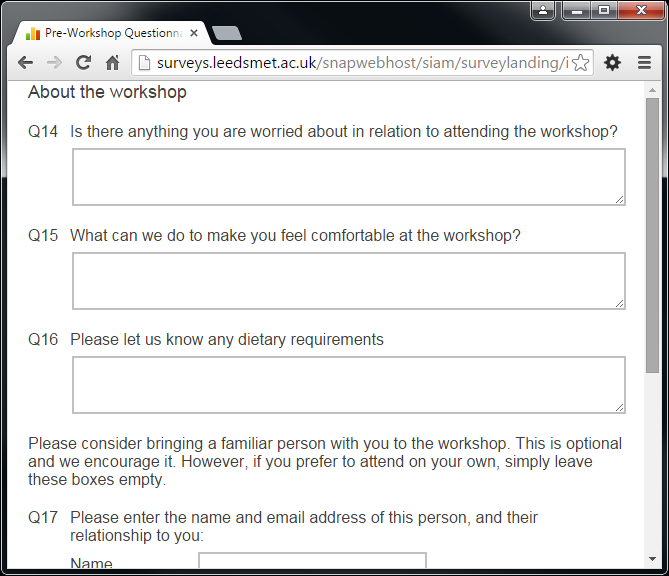

We sent questionnaires to participants asking if they had any worries or anxieties about the day and how we could make them feel more comfortable.

This felt more personal and relevant than the usual accessibility questions. In response to this, we added information about what participants could do in breaks in the workshop programme, as while some autistic people need a lot of comfort breaks, others feel lost and forced into social interaction.

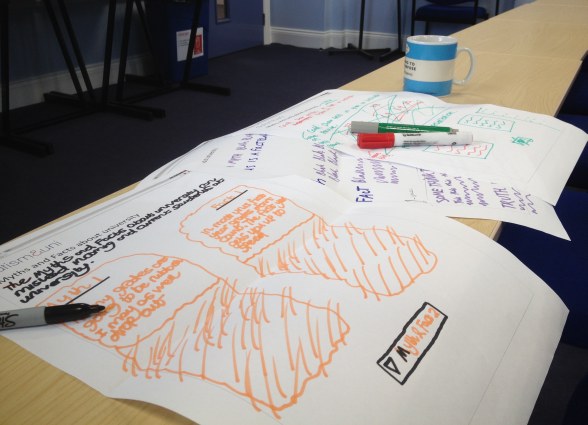

The day consisted of practical activities around trying out early toolkit prototypes and evaluating the different ways information can be presented. Participants followed walking directions on campus and created new layouts for part of the toolkit.

All participants enjoyed the activities, praising their interactive nature, and they also all commented on how good it was to actually be listened to (for once).

The most valuable parts of the day involved discussion of issues faced and strategies for coping in various situations, inside and outside of university, and it showed what a shame it is that autistic people are so rarely part of the design process – only being ‘users’ presented with products and services to test and use to help with their presumed deficits.

Participants also challenged wording that made assumptions that they would find things difficult, preferring a more neutral tone that provided information without judgement. Thankfully there was only a small amount of content that did not meet with their approval, showing we had chosen an appropriate tone and style for writing.

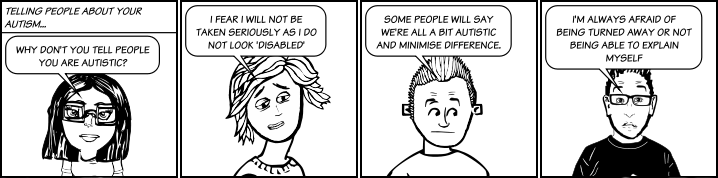

Some stereotypes were challenged, like the assumption that all autistic people think visually and prefer visual information. The test comic strip we used to show comments from real students in our surveys, using illustrations rather than photographs to protect anonymity, was popular.

Other than that, our participants strongly preferred well-structured text information to infographics or video. They told us that perhaps more visual information worked better for autistic people who also had a learning disability and struggled with reading.

Participants only wanted visual information when it specifically added something that text alone could not achieve – such as

- showing landmarks and turnings in directions to reduce ambiguity,

- images of the people they would be meeting,

- rooms they would be using, and so on.

Participants had clear preferences for how headings, quotations and other non-paragraph text should be presented and which fonts and colours did not work well for them.

We were told in no uncertain terms by our participants that they also wanted to be able to choose how they looked at information, whether it was all in one long document or broken up into chunks or in a printable format. They did not want to have this decision made for them. Also, their choice would be different depending on the content and the context in which they were using the toolkit.

One thing everyone had in common was the need for as much information as possible to be provided – and accessible ways to get at that information and process it at their own speed. Anything else, like graphics, videos, interactive activities or ‘exciting’ layouts and features would just distract them from being able to make their own route through the information in their own time, as often as they wanted. We were warned – “Stop overthinking it!”

In our Autism&Uni surveys, Wikipedia was the most popular website autistic students liked to use. Comprehensive text-based information really is vital for autistic people who have the capacity to study at university and the structure of that information is important. Shiny presentation and attempts to ‘engage’ the user generally seem to just get in the way…

The lessons we’ve learnt from this insightful workshop experience will now feed into the development and design of the interactive toolkit. We will then prototype future iterations in follow-up workshops in autumn of 2015, when the next generation of students has started their university courses.